ViiV HEALTHCARE IS AN INDEPENDENT, GLOBAL SPECIALIST HIV COMPANY

We are committed to delivering innovative new medicines for the care and treatment of people living with HIV. Our mission is to leave no person living with HIV behind.

OUR HIGHLIGHTS

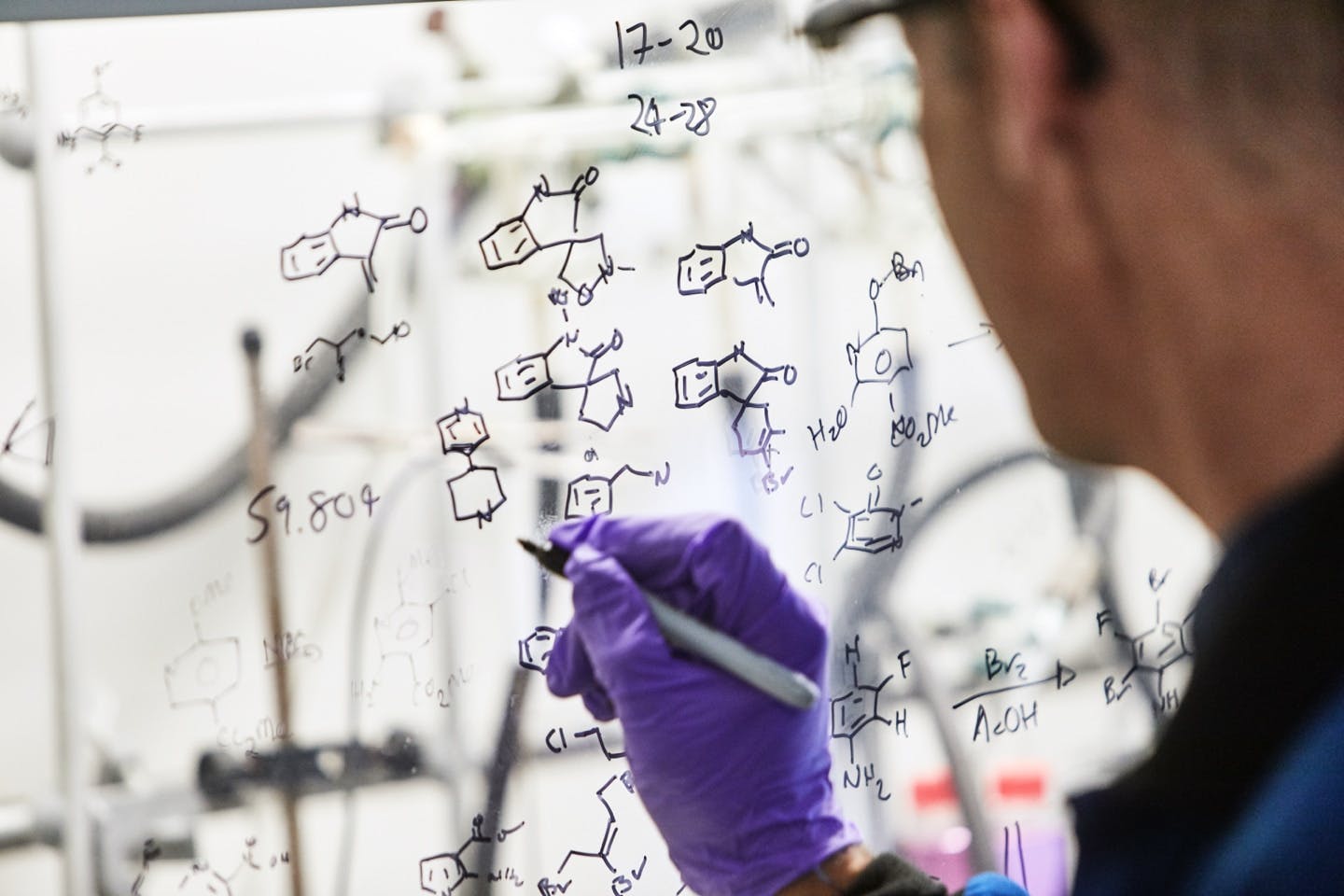

The process of identifying, creating and developing generally well-tolerated and effective innovative HIV therapies is complex and requires ongoing collaboration between research teams that work in many different areas of medicines development.

Discover the importance of representative research for HIV treatment for people living with HIV

Read about our collaboration with Shutterstock Studios for producing a gallery of images with real people living with HIV.

Community engagement

At ViiV Healthcare, we are on a mission to ensure that no person living with HIV is left behind. One of the ways we do this is by working actively with communities affected by HIV and AIDS around the world.

HIV research

When considering the heritage from our founding companies, we can proudly say that we have been involved in the development of effective treatments for HIV/AIDS from the beginning.

Ending HIV

We are the only pharmaceutical company solely focused on combating, preventing, and ultimately curing HIV and AIDS, but of course, none of what we do can be achieved alone – we believe in the power of partnership.

NP-GBL-HVX-COCO-220019 February 2024

If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor, pharmacist or nurse. This includes any possible side effects not listed in the package leaflet. You can also report side effects directly via the Yellow Card Scheme at www.mhra.gov.uk/yellowcard or search for MHRA Yellowcard in the Google Play or Apple App store. By reporting side effects, you can help provide more information on the safety of this medicine.

If you are from outside the UK, you can report adverse events to GSK/ViiV by selecting your region and market, here.